Alstadt Brewery’s Oktoberfest

⭐️⭐️⭐️

one more Märzen, why not 🍺

Alstadt Brewery’s Oktoberfest

⭐️⭐️⭐️

one more Märzen, why not 🍺

The Guardian: How Texas’s gun laws allow Mexican cartels to arm themselves to the teeth

We know that most, if not all, of these high-caliber weapons are coming from the United States and a significant amount are likely coming from Texas.

great job, Greg.

tifo at today’s Austin FC playoff game (we won, eventually!): Verde Hasta La Muerte (green to the death) ⚽️

Saturday’s beer: Goose Island Beer Co.’s Bourbon County Brand Fourteen Stout (2021)

⭐️⭐️⭐️

the eve of Austin FC’s first ever playoff game is a special occasion, right? this beer is as good as it is dark 🍺

‘Could I understand the people who rushed into the Capitol?’: George Saunders on how stories teach empathy

What our mind is learning when it reads a good story is that its current state, whatever it is, is temporary. That state is like a weather system that’s just rolled in.

Courtney Barnett, Elevator Operator, live in Austin, 2015

I come up here for perception and clarity

I like to imagine I’m playing SimCity

All the people look like ants from up here

And the wind’s the only traffic you can hear

🎵

Real Ale Brewing’s Oktoberfest

⭐️⭐️⭐️

🍺

one silver lining of long travel days is that I managed to start and finish two books: Patrick deWitt’s French Exit on the way there, & Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic on the way home. both really enjoyable (though I can’t fully recommend the deWitt) 📚

…and the view from the back porch

view from the front porch of our rental house, north of Bozeman, MT

just backed this Kickstarter project from John August (screenwriter & host of the Scriptnotes podcast): Writer Emergency Pack XL

saw Hadestown yesterday, it was wonderful. this Tiny Desk Concert can’t show the fantastic (& award-winning) set, costumes, lighting, etc., but gives a great taste of the music 🎵

people who claim, when ending a meeting earlier than scheduled, that they’re “giving you all back x minutes!!” are the equivalent of a mugger tipping you $1 from your own wallet after they rob you

Saturday’s beers:

– Elysian Brewing’s Night Owl Pumpkin Ale

– Whitestone Brewery’s Opa’s Lederhosen Oktoberfest

– TUPPS Brewery’s McKinney Oktoberfest

– Saint Arnold’s Oktoberfest

– AquaBrew’s Festbier

You have your “most wonderful time of the year” & I have mine

new post: Twitter is Bad, in which I realize (again) what many already know

Ever since the FBI raided Mar-a-Lago, I’ve gotten more and more sucked back in to Twitter. I still don’t post there, but I have an account and some old “lists” of political and legal pundit types. The excitement was real, and I wanted to know What Happened Next, As Soon As It Happened!

But I’m back on the wagon again, now. There are many specific things to criticize Twitter for, but what I really can’t stand anymore is the hyper-cynical tone that’s basically the baseline for the entire platform (at least from my view, from within my bubble, etc.).

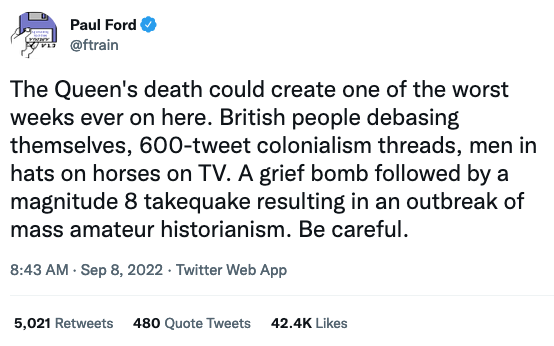

This tweet, retweeted by someone on my list, perfectly sums it up, for me:

One the one hand, that’s probably a pretty accurate description of some of the reaction to Queen Elizabeth’s death on Twitter. Yet this take warning about takes, this amateur analysis warning about amateurs, this cynicism warning about cynics is dripping with the world-weary disgust one must evidently armor oneself with just to participate “on here”.

Maybe it’s a knowing, winking, meta “joke”, at least for some of the ~48,000 people who retweeted, quoted, or “liked” it. It just made me feel gross. On the bright side, though, it snapped me out of my hypnosis.

fascinating Guardian story (from 2017!) about the astounding amount of planning for this somber day: ‘London Bridge is down’: the secret plan for the days after the Queen’s death

a modern-day witch casting spells in front of the BBC & everyone: Florence + the Machine, Free

The Guardian: Barbara Ehrenreich, author who resisted injustice, dies aged 81

“She was never much for thoughts and prayers, but you can honor her memory by loving one another, and by fighting like hell.”

Goldfrapp, Road to Somewhere

Walking down the Mercer Street, been a long hot summer

Rain like daggers coming down on me

Get a feeling it’s too late, but alone, together

Could be we might start it up all over again

Saturday’s beer: Brouwerij Bosteels’ Tripel Karmeliet

⭐️⭐️⭐️

lovely evening for some soccer

The Onion: Underwhelming Fantasy Novel Starts With Map Of Ohio

Huber Heights, hell yeah

donated to Movement Voter Project’s Texas Fund. really like their emphasis on building for the long-term, beyond the next election (but also hope this helps the next election 😅)

no, you watched Valley Girl tonight

is this movie in 3D?

no, but your face is

I’m not a “self-motivation hard-case”, as he calls it, but the feeing of escape from giving up on something tough described in this Raptitude post is one I can sure recognize. what an insight

this piece about “people recalibrating their relationships to their jobs” was ok, but what struck me was disagreeing with Maeve here:

Maeve… worries that she will never earn enough. “A hardback book is 20 quid, a pint is a fiver – so many pleasures in life are so expensive.”

new post: One Year On: How We Do It, in which I acknowledge that it’s been a year since our tragic loss, and try to give a more full answer to “how are you, really?” than I can in casual conversation

Saturday, July 30, will mark the one-year anniversary of the car crash that took our daughter Mary from the world. We aren’t planning on “doing” anything to mark the date, because that date isn’t something we want to focus on. Not this year, at least. Mary’s birthday on April 4, or other holidays that we were lucky enough to share with her 20-plus times, or just any ordinary day when we miss her (every ordinary day): those are what we want to focus on. Her life, not her death.

So we’re not commemorating it, but it still exists. It’s a milestone on this road: one calendar year. All the things that happen on calendar dates, like that birthday and those holidays, have now come and gone once each. Some of them weren’t so bad, some of them we had to white-knuckle it, most of them were less rough than we’d braced ourselves for. Next up: the second of all those dates, I guess.

What’s great about the one-year mark is that that’s when we get our Certificate of Being Done from the Office of Bereavement & Loss, and we won’t have to grieve or be sad anymore. What a relief! When people ask us how we are from now on, we can just say “Fine! You?” (with varying levels of sincerity but basically actually meaning it), just like we could before July 30, 2021.

That’s obviously not true, of course. And I was going to add something like, “though I’d give my right arm and every penny in the bank if it were,” but that’s not really true, either. What we’ve learned – what a lot of people already know, but we didn’t, not like we do now – is that grief is the obverse of love. It’s not easy, but it’s that simple: it’s just the other side of the coin. The loss hurts in direct proportion to how much you loved the one who’s gone. A more “natural” timeline or other circumstances may ease that: losing someone in their 90s whose death frees them from chronic pain after a long illness might hurt less than losing a young woman whose adult life had barely begun. (Or it might be every bit as bad; there’s no accounting for this stuff.) But to forego the grief and heartbreak would require cancelling out the love that came before, which is as unthinkable as it is impossible.

So what does a year mean? Not the end of this “grief journey” (as they call it), any more than two years, or ten, or fifty will mean the end. But the pain is less terrible, on a daily basis, than it was those first days, weeks, and months. A friend in our grief support group has put it as well as I’ve heard anyone: it doesn’t get easier, but it gets softer. Now, we can go about our lives as if they were normal, in bursts of varying length. The length of a movie, or a meal, or a soccer game. An afternoon, a work meeting, an exercise class.

And in between those bursts, we remember. And while remembering the loss hurts, the memories and thoughts of Mary aren’t a bad thing. Not at all. They’re often sweet, if sometimes with a healthy dose of bitter; sometimes they’re just plain sad. But they are always – always – welcome. Trying to not think (or feel) about her isn’t what we want, or need.

The same goes – one hundred percent of the time every single day – for anyone who wants to share memories or thoughts about her with us. You cannot make us sad, or mess up our day, or bring us down in any way, at all, by talking to us about our Mary, or missing her. I promise. Another support-group friend had someone ask if they should share with her some old pictures of her daughter that they’d come across. They were afraid the pictures, and the memories, would be too painful. Yes, share them, of course, she told them. I never get any ‘new’ pictures of her, otherwise.

That support group, by the way, is run by The Christi Center, and it has been a true lifesaver. (It’s an Austin/Central Texas organization; we don’t have experience with The Compassionate Friends, but I understand it’s similar, and has chapters across the country.) Hearing other peoples’ child-loss experiences, across a huge variety of circumstances, ages, timelines, etc., has strengthened us and helped give us perspective. We’ve read a (still-growing) stack of grief literature, which has also been helpful, but direct communication, even by Zoom, with people who are on this same damned road has been essential.

People wonder sometimes “how we do it.” How we got through a whole year, or how we got through yesterday, or how we’re going to get through tomorrow. How we can be so “strong”. The blunt truth is that, leaving aside self-destructive options that would only cause more pain, there just isn’t a choice. I said before that it gets “softer”, but that’s a generality, and a polite one. Most of the time, on most days, we’re about as okay as anyone, but sometimes we’re hit with the full force of this absolutely horrific reality – what your mind might give you a glimpse of if you try to imagine being in our shoes – and it really hurts. Of course it does. But it doesn’t last. It can’t. And then we go on, because that’s all there is to do.

The best analogy I’ve heard is that this level of loss is like an amputation. An amputation of part of your heart, in a figurative, non-cardiac sense, obviously. (One thing that’s weird about this figurative amputation is that it’s not externally visible. If I lost a leg, people would see it, and accommodate or acknowledge my disability, or at the very least know that something serious happened to me. Not so with this loss. Do the new hires on my team at work know? Only if someone told them. Do I want someone to tell them? I’m not even sure. It’s weird, is all I’m saying.)

I think the amputation analogy applies pretty well to the “how do you do it” question, too. If you lost a leg: how would you get by after that? Well, your life would be drastically altered, and it would really suck sometimes, and it would really, literally hurt sometimes. But you’d still be here, and there would still be a life to live. One way or another, you’d get through this day, and you’d go to bed. Maybe you would have an okay night, or maybe you would lie awake and feel sad for what you’d lost. You’d wish you could hug your leg one more time, or laugh with it, or make it its favorite dinner, or help it plan its wedding someday. But either way, the alarm would go off the next morning, and you’d get up, and you’d do it again.

Lastly, we sure haven’t been doing it alone. In addition to the weekly support group, the love, thoughts, and kind words we continue to get from family, friends (of ours, and of Mary’s), and everyone mean a lot to us, and help us so much. Thank you.

amazing. ‘Like a public shaming’: a night with the eco-activists deflating SUV tires

“Why do you need an SUV, especially in New York? It’s a vanity thing. You have freedom of choice, sure, but you don’t have freedom from consequences.”

new from Metric: Doomscroller

is a 10 & a half minute song a little long, especially for the first song on the album? NOPE

I can’t seem to shut it down

until the worst is over

& it’s never over

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén